When I taught the class Four Season Food Production at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College, the first project of the semester was a 100 Mile Food Plan. Working in groups, the students were to imagine their food supply was going to be disrupted and their only food, beginning January 1, was going to be from local sources. The project was due in mid-September, so they were to feel fortunate that they had this heads-up months in advance. In real life disruptions occur with increasing frequency with no advance warning. They would have to source their food within a 100 mile radius of where they lived.

When I taught the class Four Season Food Production at J. Sargeant Reynolds Community College, the first project of the semester was a 100 Mile Food Plan. Working in groups, the students were to imagine their food supply was going to be disrupted and their only food, beginning January 1, was going to be from local sources. The project was due in mid-September, so they were to feel fortunate that they had this heads-up months in advance. In real life disruptions occur with increasing frequency with no advance warning. They would have to source their food within a 100 mile radius of where they lived.

The students would need to find sources for winter food and be able to store it or preserve it now. Or, they would need to know a farm where they could buy it as needed, since the grocery stores would be closed. They could grow it themselves, of course, but that would take awhile and winter was coming on. This was a year-long plan, so growing it themselves would be planned in. If the animal products in their plan depended on feed shipped in and not grown locally, that would be a consideration.

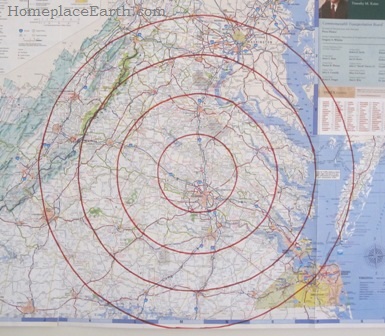

My intent in assigning this project was to acquaint them with the local food system. I wanted to get them out to the farmers markets to talk with the farmers and find out what was available. I also wanted them to think about exactly what it was they ate and how much they needed for a year. They received extra credit if they brought in a highway map of Virginia with their location pinpointed and circles at 25, 50, 75, and 100 miles away. It had to be a highway map so that it showed all the localities. When they first thought of this 100 mile limit, many students thought it would severely limit their choices until they actually put the circles on a map. Even if you are not familiar with Virginia, you can see from my map that there are mountains on the left and the ocean on the right—all within 100 miles from my house as the crow flies. The area goes north into Maryland and dips into North Carolina to the south. Make a map of your own and see what you would have to choose from.

This project sure was an ice-breaker. One thing that always happened in my classes was that people talked to each other. Each group had to assess the strengths of each of its members. Someone may have land available for future growing and others may have money, tools, skills, storage facilities, or muscle to contribute to each “community”. They would need to show on a chart what foods they found and where, how much they would need of each food for the year for their group, and how it would be stored or preserved. I also wanted their comments on what strengths and weaknesses they found in our present local food system. This generated plenty of discussion about what would happen if everyone had to suddenly depend on these local sources and what, if any, changes in their lifestyle and diet this project encouraged. I always enjoyed the interaction among everyone. I remember one group that had both a long-time vegan and a young woman whose family ate mostly meat. When you are planning for a community, everyone must be considered.

When I first started teaching at the college in 1999, farmers markets were few and far between. It amazes me how many there are in 2013, with the number growing each year. I was one of the founding farmers of the Ashland Farmers Market. I stopped selling vegetables after the 2001 season to concentrate on teaching in order to put more knowledgeable consumers and producers at the markets. The produce, meat, eggs, and honey sold at the Ashland market must have been grown within a 30 mile radius of the town. If shown as a circle on my map, it would be just outside the inner circle. Most markets don’t have such a limit. Besides farmers markets, there are many other options for people to connect with local growers. You can find sources for food grown in your area by checking www.localharvest.org.

When I first started teaching at the college in 1999, farmers markets were few and far between. It amazes me how many there are in 2013, with the number growing each year. I was one of the founding farmers of the Ashland Farmers Market. I stopped selling vegetables after the 2001 season to concentrate on teaching in order to put more knowledgeable consumers and producers at the markets. The produce, meat, eggs, and honey sold at the Ashland market must have been grown within a 30 mile radius of the town. If shown as a circle on my map, it would be just outside the inner circle. Most markets don’t have such a limit. Besides farmers markets, there are many other options for people to connect with local growers. You can find sources for food grown in your area by checking www.localharvest.org.

The two items my students had the hardest time finding were grains and cooking oil. There was much discussion about the possibility of making oil from the black walnuts that are prevalent in the area. That was before the Piteba, a home-scale oil press, was available. Even with that press, I’m sure the novelty of making oil from walnuts would wear off quickly. There was also much discussion about a source for salt. To really learn, you need to begin with questions and my students generated lots of questions while doing this project. You are probably familiar with Barbara Kingsolver’s book Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, a story of one family eating locally for a year. Once that book came out in 2007, many people began to think seriously about where their food comes from. About the same time, the book Plenty by Canadians Alisa Smith and J.B. Mackinnon was published. This couple had fewer resources than Kingsolver’s family did. They ate a lot of potatoes and tried their hand at sauerkraut which smelled up their small apartment. I encourage you to read both books.

It can be quite a shock to your system to change your food supply suddenly. It is much better to ease into it and make changes gradually if you want them to last. The change needs to start in your mind, and that’s why I had my students do this project. I didn’t expect them to come up with all the answers to a plan that could be implemented right away. That would take much more planning. I did expect them to begin to question their diets and food sources. It certainly got them to focus the rest of the semester on actually growing their own food.

The next project was on cover crops and then there was one about designing a season extension structure to cover a 100 ft² bed. Although it was not required to build the structure they designed, many students did and managed to get it planted that fall. With the first project, all agreed that if we actually had to depend solely on local supplies, there would not be enough food for everyone. With that in mind, they went ahead and built their structure. For the last project, each student was assigned a vegetable and had to write a newsletter about it as if they were a farm and this was their featured product for sale. I left the college in 2010 to be able to address a larger community. The classes continue with my daughter Betsy Trice as the instructor. Betsy has put her own spin on the classes, but she still assigns the 100 Mile Food Plan. If all the grocery stores were to close on January 1, where would your food come from?